Even though there have been many studies done about the benefits of mindfulness and its impact on the brain activity, there is no exact answer for why mindfulness has such beneficial effects on us. The research is still on-going and in the initial stages of development. However, here we present some of the possible theories of what happens to our brain when we regularly practice mindfulness.

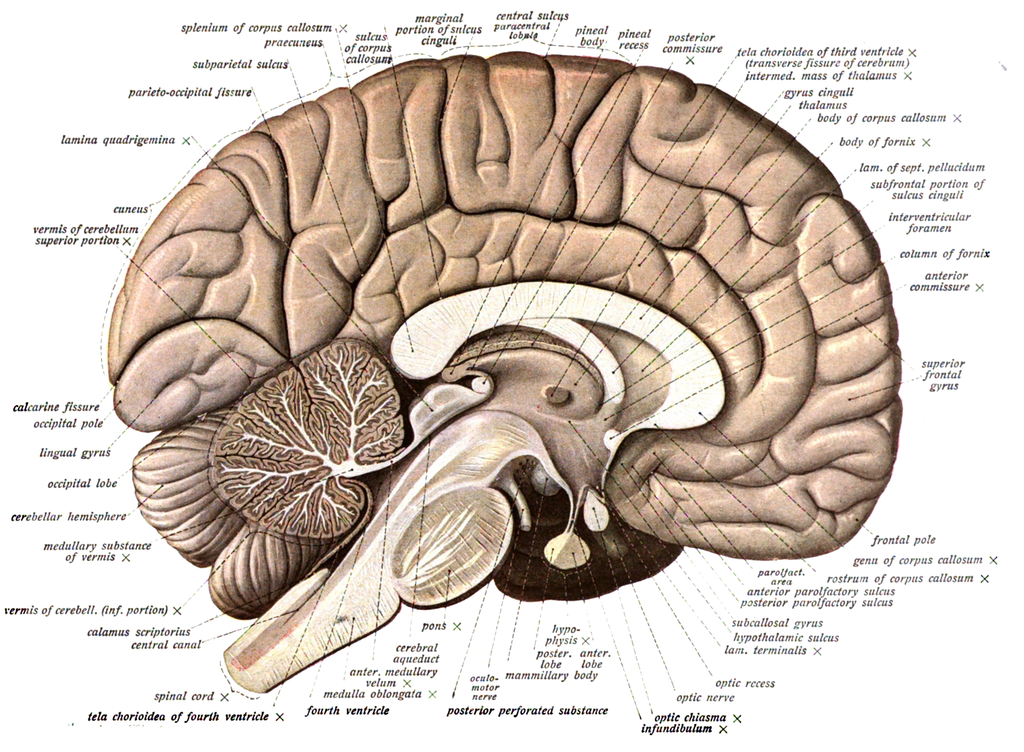

One of the studies has shown that after the eight-week mindfulness practice course the participants’ amygdala, which is associated with stress, fear, and “fight or flight” responses, seems to decrease. So while amygdala seemed to shrink, the pre-frontal cortex, associated with higher brain functions like concentration, awareness, and decision-making, seemed to increase in size. Moreover, the “functional connectivity” between these regions also changed – the connection between amygdala and other brain areas got weaker, while the connection between the areas associated with concentration and attention got stronger, and the scale of these changes corresponds with the number of hours the meditation has been practices – the bigger the number, the greater the changes. “The picture we have is that mindfulness practice increases one’s ability to recruit higher order, pre-frontal cortex regions in order to down-regulate lower-order brain activity,” – Adrienne Taren, a researcher studying mindfulness at the University of Pittsburgh. This means that our primal responses to stress are actually supressed by more thoughtful ones. It is this disconnection of the rest of the brain from its “stress centres” that seems to be at the root of many physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing benefits of mindfulness practice. “I’m definitely not saying mindfulness can cure HIV or prevent heart disease. But we do see a reduction in biomarkers of stress and inflammation. Markers like C-reactive proteins, interleukin 6 and cortisol – all of which are associated with disease”, – Adrienne Taren.

Moreover, another study has shown that “two regions that are normally functionally connected, the anterior cingulate cortex (associated with the unpleasantness of pain) and parts of the prefrontal cortex, appear to become “uncoupled” in meditators”[1]. The meditators did not refrain from experiencing pain – they simply did not engage into thought processes associated with experiencing pain which might have been the reason behind many meditators reporting feeling significantly less pain than non-meditators. Interestingly, the meditators did not only feel less pain during the meditation – it seems that “[T]here is just a huge difference in their brains. There is no question expert meditators’ baseline states are different,” – Joshua Grant, a postdoc at the Max Plank Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany.

Another study on expert meditators (who have done more than 40,000 hours of meditaton practice) shows that “their resting brain looks similar, when scanned, to the way a normal person’s does when he or she is meditating. At this level of expertise, the pre-frontal cortex is no longer bigger than expected. In fact, its size and activity start to decrease again, says Taren. “It’s as if that way of thinking has becomes the default, it is automatic – it doesn’t require any concentration””[2], emphasising the powerful potential of meditation to dramatically and irrevocably change our physiology, thus changing our behaviour and even personality.